The art of cartography, by Marcelo Roqué

The art of cartography, or how to make a map, appears at the dawn of humanity and predates writing.

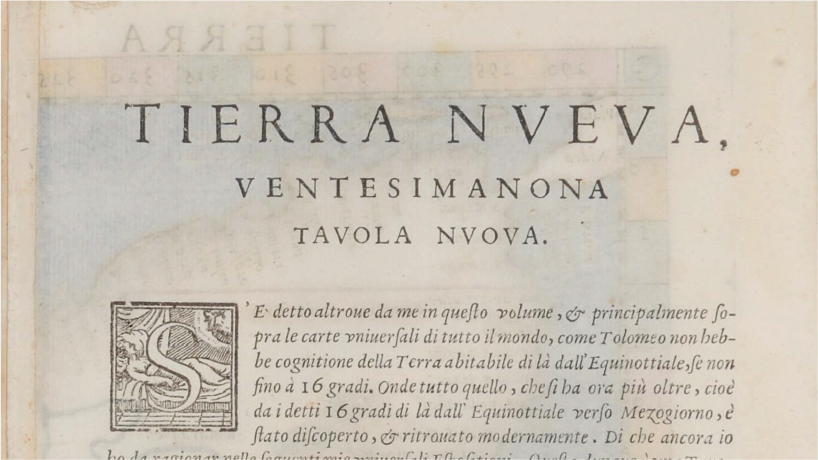

It is in the Catalan Atlas by the Majorcan Cresques or in Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map, where the name «America» first appears on a map depicting parts of Paraguay and partially Brazil and Argentina.

With the invention of the printing press, the reproduction of cartography began, first with woodcut matrices. The engraving of these images was later perfected using copper, bronze, and finally steel plates. The invention of lithography allowed for higher-quality map production.

Initially, the surveying of a map depended on pedestrian measurements or the cartographer would rely on the time taken between two points or the distance covered by a wheel on straight lines, measurements used for drafting the map. A planar geometry was applied using known reference points, such as a church tower, a hill, a river bend, or a coastal point.

Mariners used the height of stars and celestial bodies with quadrants, sextants, and astrolabes to measure latitudes. The great difficulty was determining longitude, from a reference meridian up to the invention of precise mechanical clocks and astronomical tables.

The cartographer M. Waldseemüller seems to have invented a prototype theodolite for measuring horizontal and vertical angles, which is why his surveys in the Rhine plain are the best of his time.

Great European cartography enriched itself in the 16th and 17th centuries through the creation of beautiful maps, sometimes hand-colored in atlases. The main publishers were in the Netherlands, Flanders, London, and Paris.

In the 17th century, there began a desire to know more precisely the shape and dimensions of the Earth. The first step was measuring an arc of the Earth’s surface. The following instruments were available: the telescope, the pendulum clock, and the logarithmic tables. Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian astronomer settled in France, perfected modern methods for cartographic science. By the mid-18th century, artistic and artisanal cartography ended and scientific cartography began.

Thus, cartography starts with art and craftsmanship and ends with science and technology. But isn’t the word for art in Greek «Techne»?

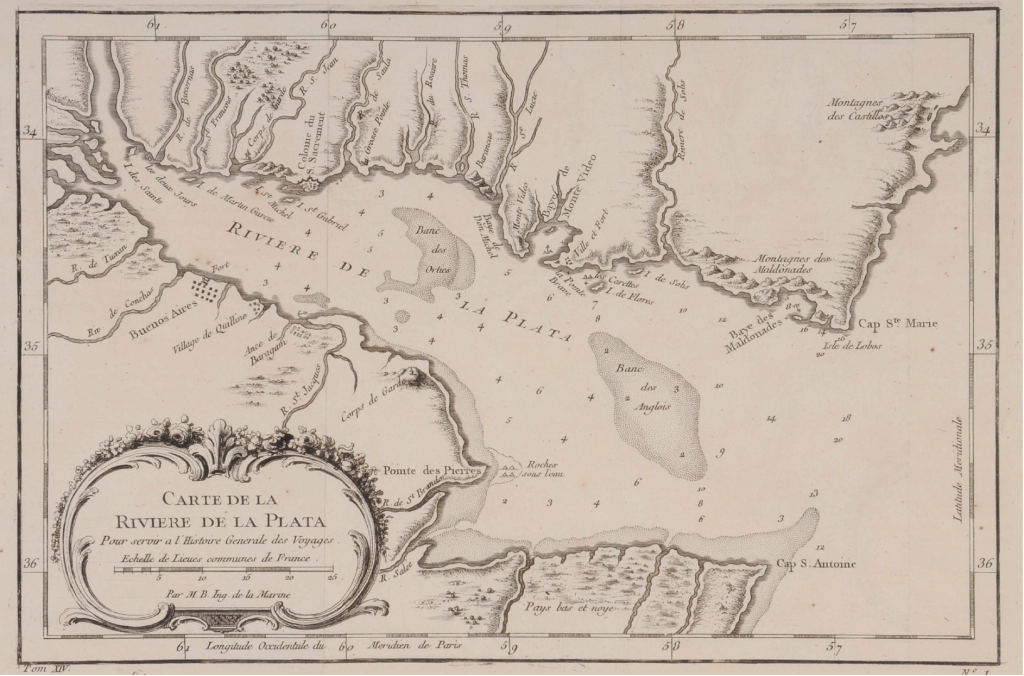

Our maps were born with the discovery of the American continent and within a few years, maps of the Caribbean and South America began to be drawn. The coasts of our country appeared with some place names. The Río de la Plata was the first to be charted. Soon we also see the Paraná River and some tributaries. The Jesuits conducted surveys of our riverine coastline and their missions in Paraguay along with the Tucumán region. English, Dutch, and French cartographers published colored maps of our lands in atlases of various sizes.

A few years after the founding of our cities, their names already appeared on South American maps, alongside the main rivers which were the primary penetration routes for the conquistadors. Thus, Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago, Córdoba, Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, and rivers like Xanaes, Carcarañá, and others appear.

A few years after the founding of our cities, their names already appeared on South American maps, alongside the main rivers which were the primary penetration routes for the conquistadors. Thus, Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago, Córdoba, Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, and rivers like Xanaes, Carcarañá, and others appear.

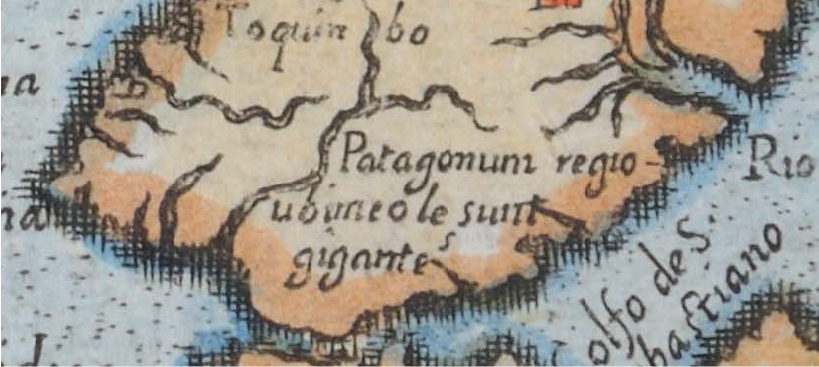

Until the late 19th century, Patagonia was depicted as “terra nullius”, land of no one, with various names: Land of the Patagons, Patagonia, Magellanic Land, Chica, or Chicuito. The boundary between Spanish possessions and Brazil was fluctuating.

In the large South American maps drawn between 1775 and 1850, measuring between 80 centimeters and nearly two meters, mountains, rivers, settlements, post stations, and royal roads were depicted with considerable precision. Among these valuable maps, we can mention those by the Spaniard Cano y Olmedilla from the late 18th century, the American Aaron Arrowsmith, the Englishman John Arrowsmith, among others. Notably, these authors’ works accurately depicted the royal road from Buenos Aires to Santa Fe de Bogotá and Cartagena de Indias on the Caribbean Sea, passing through Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. The maps also show the royal road from Buenos Aires to Santiago de Chile. Comparing these valuable cartographic pieces reveals changes in the names of post stations or their disappearance in favor of others.

Almost all the cartographers whose works are presented in this exhibition were inspired by surveys conducted by other geographers, hence repeating errors in the coastal outlines, jurisdictional boundaries, or place names.